Our understanding of mental illness and how people suffer from it has come a long way over the years.

In previous centuries, people were shunned, locked away, often restrained and given involuntary treatments.

While their methods were still far below our modern standards, a hospital in Lincoln would have been the best place in the country for people afflicted with mental illness in the early 1800s.

Lincoln Lunatic Asylum – a name that certainly wouldn’t be considered politically correct today – was opened in 1820.

The grand Greek revival building was set in walled gardens known as the Lawn on Union Road, opposite Lincoln Castle.

However, patients in the complex weren’t meant to feel as though they were caged – the walls were out of sight below the hills brow, giving a feeling of freedom.

There were less than 100 patients, addressing the common issue with overcrowding in asylums.

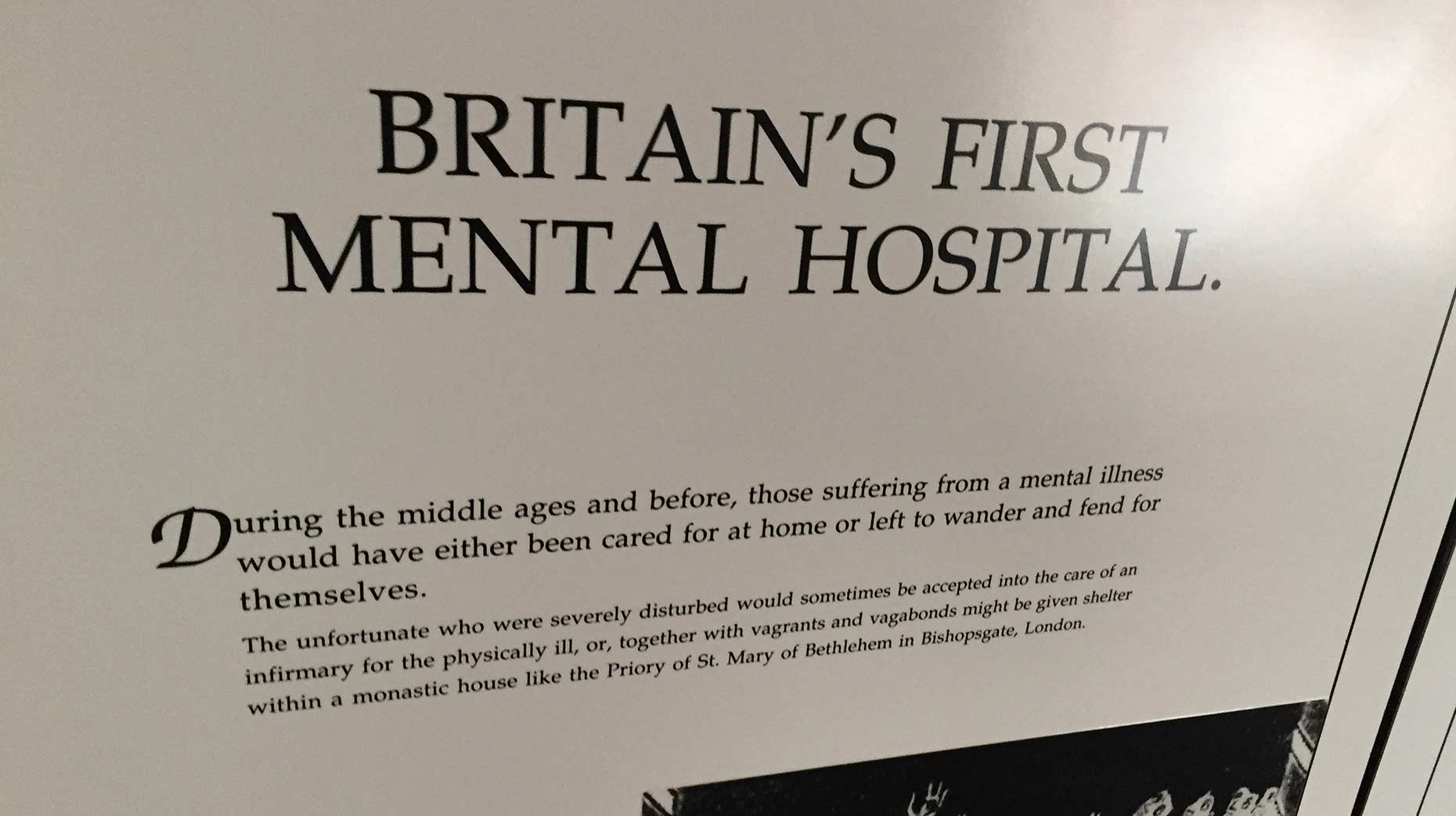

An information board inside the building | Photo: Emily Norton for The Lincolnite

The purpose-built hospital had separate male and female wings, with areas for exercise and work – ‘the cornerstone of recovery’ – while alcohol was discouraged.

Unusually for mental hospitals of the time, it was aiming to reduce the amount of restraints used – perhaps spurred by the death of a patient who had been tragically found dead while in a straight jacket.

In 1830, restraints were used for a total of 25,485 hours, but this soon fell.

The heaviest of the iron handcuffs were destroyed to prevent their use, followed by finger-confining restraints.

Soon, only minimal restraints were allowed as “the object was not punishment, but security”. There were entire days when none were used in the hospital.

Although patients’ room quality depended on how much they had paid, even the poorest who relied on charity received sunny rooms.

The hospital’s Vice President and doctor Edward Charlesworth was one of the main advocates of humane treatment.

Around 1835, he met a promising young Louth doctor called Robert Gardiner Hill, who had radical ideas to get rid of the restraints completely. Charlesworth urged him to apply for the asylum’s Medical Supervisor role.

This wasn’t an easy change. Records show that there were hundreds of instances when they were still used in his first year – ostensibly to protect staff and the patients themselves from harm.

Robert Gardiner Hill, who was instrumental in the reforms at Lincoln Lunatic Asylum

Employees complained that they wanted higher pay due to the increasingly dangerous work.

However, Hill persisted in his methods, hammering the new techniques into his employees.

In one case, an elderly man had been chained up to prevent him picking at his sores. Hill had him released and set someone to watch him instead, which had the same effect.

Hygiene improved since inmates were now able to properly clean themselves.

By 1837, restraints were done away with almost completely – a first for an asylum in England – and replaced with “personal undivided attention towards the patients”.

That year, they were only employed for 28 hours – a fraction of the previous 25,485.

The chaos that wardens feared would erupt without restraints didn’t happen, and records say patients responded well to the new regime.

Hill also cracked down on “glutting and guzzling” – getting drunk at work – amongst the staff, which led to poor treatment.

Other physicians and people involved in the justice system took an interest in the pioneering work.

Practitioners carried out similar experiments – some successful – in larger asylums in London and York, which proved this worked.

The ideas were also gathering steam around the country, with ‘Mad’ King George III receiving a variety of therapeutic treatments to deal with his mental illness.

But Hill’s tenure at the Lincoln hospital didn’t last long. In 1840, he realised he was losing control of the attendants, and was forced to resign.

He spent years bitter about the end of his experiment and arguing over who deserved credit for non-restraint treatments.

Although mental health treatment still had a long way to go, the methods which spread across the country proved transformative.

Hill’s obituary concluded that the non-restraint method yielded ‘momentous results to the insane’.

The institution evolved into the Lincoln Lunatic Hospital in 1905, and The Lawn Hospital in 1921.

It later passed into the NHS’ hands, and was bought by the City of Lincoln Council after it ceased being a hospital. The building now belongs to Stokes, with a coffee shop on the ground floor.

Its history as an asylum is best preserved in the Asylum Steampunk Festival, which was first based at the historic building and has now expanded across the Bailgate.

A statue of Edward Charlesworth still stands in the ground today.