Parliament returned from recess this week planning to talk about the misuse of laser pens, but instead the House of Commons Chamber was packed to the rafters to talk about the recent military action Britain took with the USA and France in Syria.

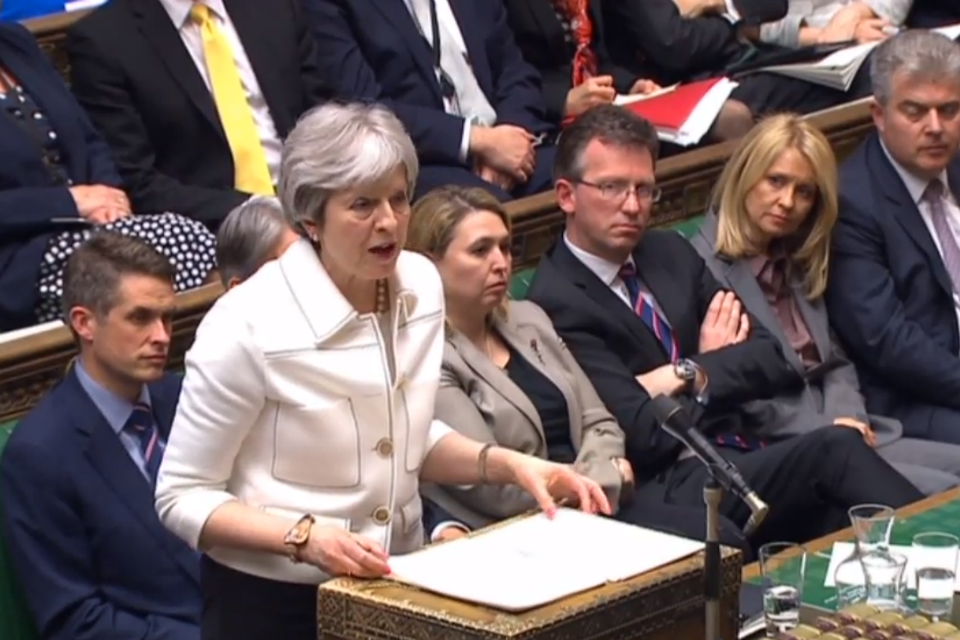

Theresa May’s opening statement on the issue made clear that it was one not taken lightly – no Prime Minister could ever put British service men and women’s lives in danger lightly. But she also made a case that was described across the House as compelling.

The actions of President Bashar al-Assad have shocked the world – repeatedly he has used chemical weapons on his own people, gassing children who have died horrible, unnecessary deaths in a civil war that the Assad regime is winning anyway.

It was to stop this behaviour, that makes the use of illegal chemical weapons a normal part of conflict, that Britain, France and America launched overnight attacks on facilities that research or enable their use.

Allowing such international norms to be degraded would put Britain in clear danger. We’ve already seen the attempted murder of the Skripals in Salisbury using a chemical nerve agent – that crime was on a far smaller scale than the atrocities in Syria, but the comparison is a clear one.

It is in all our interests to live in a world that is free from chemical weapons.

When President Assad used them previously, Russia said they would steward the destruction of all stocks, but have not done so.

Russia has also vetoed UN resolutions that would condemn Syria, and effectively is vetoing the usual methods of global condemnation that can be used to back military action.

In short, Syria is behaving in a way that is clearly illegal, and Russia has a veto on internationally accredited action. Britain has placed itself firmly on the side of helpless men, women and children in Syria in a limited, targeted military strike with our allies; Russia has placed itself firmly on a very different plain.

This was very much the mood in Parliament, where a vote on the issue was won by a majority of several hundred. As one Labour MP put it, had the Prime Minister recalled Parliament early and asked for her vote, “she would have had it”. And that question of recalling Parliament over a small-scale, surgical use of eight of our missiles is surely redundant: anyone who understands such tactics knows that a country must be able to behave in secret rather than give up information that could compromise our troops’ safety. To suggest otherwise is wilfully naïve.

What Parliament did have was the chance, after the fact, to hold the Prime Minister to account. MPs were able to assess evidence that has convinced dozens of global leaders and international organisations, and to see more of that evidence than would have been safely possible before the action was taken.

Some people have chosen to support the conspiracy theories promoted ultimately by the Kremlin. To do so is to ignore the facts, and the uniquely precise nature of the action Theresa May chose to take to safeguard global security and the lives of innocent civilians.