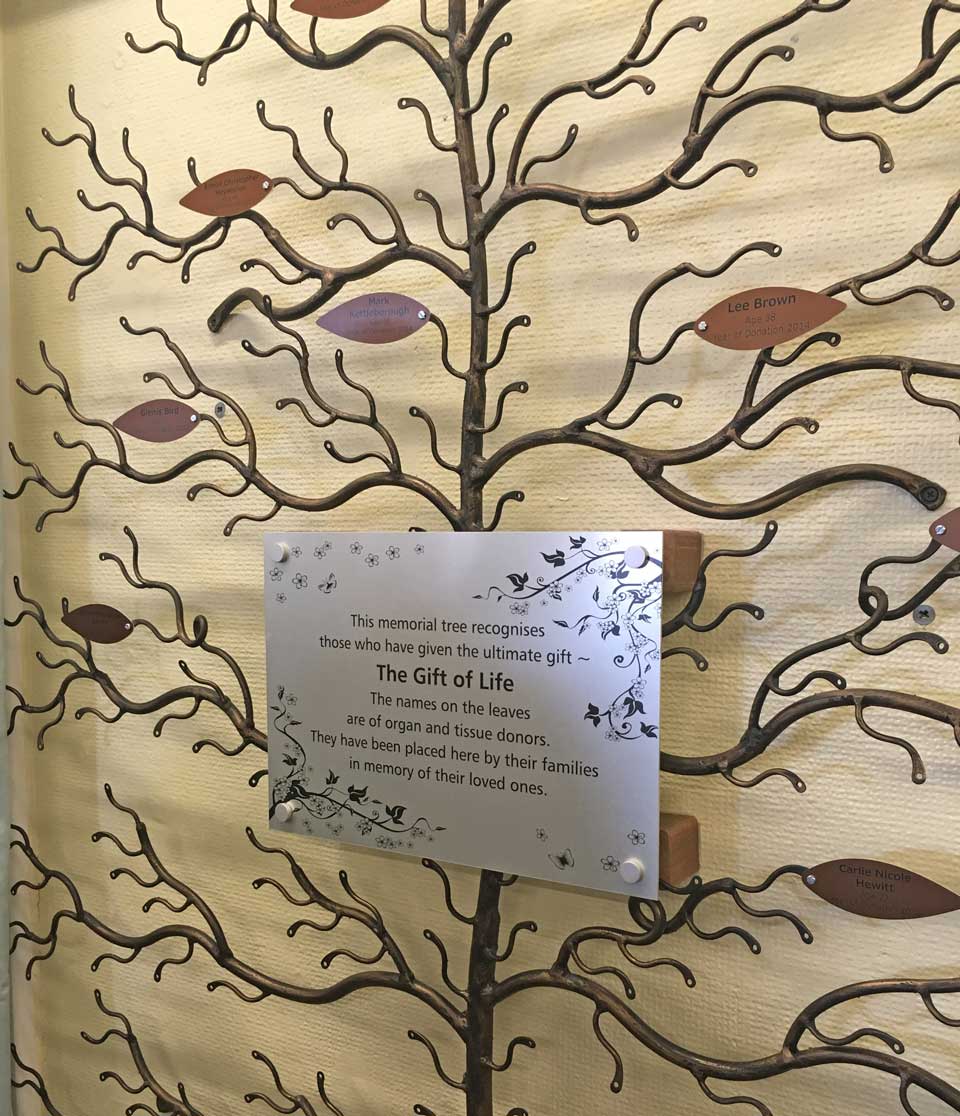

At Boston’s Pilgrim Hospital last week, the Bishop of Grantham unveiled an organ donation tree, marking the gift given by all those who have donated their organs so that others might live more fulfilling lives. It is, by any definition, a gift that goes beyond anything that money can buy. And it’s a gift that millions need and few are prepared to give.

The tree at Pilgrim is, of course, a commemoration but also a symbolic advert for more people to get behind the organ donation initiative. For decades, it’s been an opt-in measure: those who, for whatever reason, have signed up to donate some or all of their useful organs on their death have done amazing things, but the system has been hampered simply by the small numbers of people who are ever asked, and the consequently even smaller number that say yes.

This week in Westminster, the Government will, however, back a literally life-changing proposal for hundreds of thousands of people in the UK, which I sincerely hope all parties will back. Rather than opt-in, the system will be flipped to opt-out.

Anyone who feels they would rather not donate a specific or all their organs will be able to retain just as much control as now, but the assumption will be that people are willing to aid medical science to help others.

Not everyone, of course, will be affected, but the overall impact will be enormous. As has already been seen in Wales, it’s a shift that results in radically different lives for huge numbers.

Why are levels of organ donation too low in the first place? The answer is largely down to both logistics and inertia: people aren’t asked often enough, and there is no easy way to scale up the process of asking. Adverts, over many decades, have had limited effect.

This is not for a second to downplay the significance of the decision being made: to donate an organ will remain a choice and it will never happen if a potential donor has said they don’t want to.

These proposals strike, for me, the right balance: they ensure that people who care passionately about not donating an organ can still make sure they never do, but it also says that those who can’t be bothered to take the time out to fill in a very simply form are probably not passionate about avoiding something which, of course, will only have any impact on them after their own death.

That means religious communities, for instance, who often have strongly held views on such matters, will easily be able to use their own networks to opt out large numbers of people – but it also means that good on a huge scale will be done with relatively little change.

Indeed, a challenge will be to make sure the NHS is prepared to tackle with the hoped-for surge in organs now available to help save lives. That – for once – would be a nice problem to have.