New Year’s in Britain has a long, winding and strange history, one with supposed pagan undertones and Christian adaptation. Given its current wild celebration, perhaps it is fitting that it has returned to the date set in stone by the pagan Caesar that was bemoaned and belittled by the church for over a thousand years.

From many to one

The history of our modern New Year’s begins with the ancient Romans. In the Roman calendar, the year officially began with the appointment of the new consuls. This occurred at various dates under the old Roman republic, but was finally altered to the 1st of January in 145 B.C.

This date was officially set in stone by Julius Caesar in 45 B.C and would remain the start of the New Year for the rest of the history of the Western Roman world. The significance of January 1st went beyond simply the appointment of the new consuls.

As January was associated with the Roman god Janus, a two-faced deity, the beginning of that month served a fitting break –the ability to look back on the previous year, while looking forward to the New Year which laid ahead.

A statue representing Janus Bifrons in the Vatican Museums

As the Western Roman world crumbled in the later 4th and early 5th centuries, however, the date of the New Year began to shift. As Germanic hordes conquered the old provinces, they brought with them their own customs. Certain areas where a semblance of the old Roman system survived, such as Lincoln, probably maintained the 1st of January date, but by the 6th century it had certainly disappeared.

The general consensus amongst the post-Roman world and newly Christian world was that the Roman New Year’s was a pagan festival and therefore it should be abolished. This was firmly put in stone at the Council of Tours in 567, where the celebration of New Year’s on that date was condemned and Easter the recommended choice.

From this point on, the date of the New Year’s went on a strange journey across Europe, but especially in Britain. To the Anglo-Saxon’s, the New Year shifted the 25th of December and Christmas. It seemed a fitting date, seeing as it coincided with the birth of Jesus Christ. Elsewhere in Europe, however, it varied widely by kingdom – from the 2nd of December, to the 25th of March, or even the 1st of September.

The 25th of December remained the official start of the New Year in England until 1066. After this it shifted back to 1st January. This shift was made by decree of William the Conqueror, who wished for the New Year to coincide with his coronation. He had been crowned amongst wild celebration on Christmas Day and felt that January 1st (which marked the date of Jesus’s circumcision – Christmas plus 8 days) fit the bill.

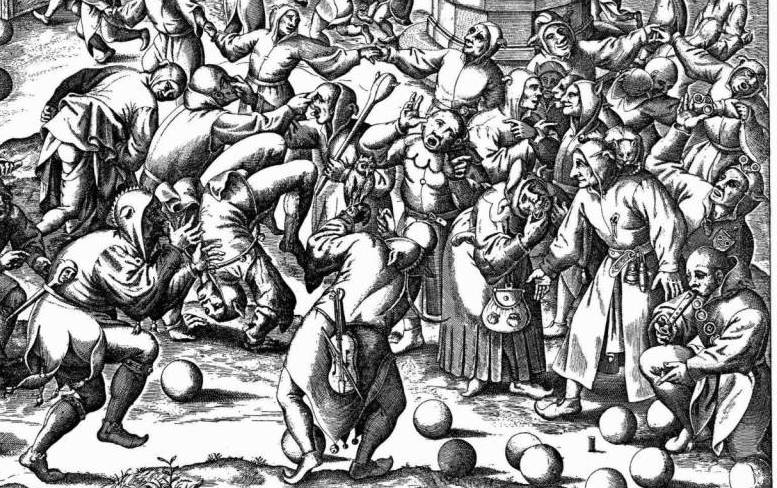

It should be noted, however, that as January 1st was condemned as a pagan day by the Council of Tours, and England was still a devoutly Catholic state, this was only the start of the civic New Year’s, and not the religious one. Indeed, the mocking of the pagan January 1st in this period is best exemplified by the ‘Feast of Fools’ I mentioned in my last column – where drunken priests would sing bawdy songs and wear crude masks.

Eventually by the 12th century (1155 to be precise), England decided its New Year’s should coincide with the other kingdoms of Europe for general ease. Thus, by this time the New Year’s was changed again – from 1st January to 25th March. The significance of the date was the Feast of the Annunciation of Our Lord to the Blessed Virgin Mary (or Lady Day if that’s too much of a mouth full to say). This was the supposed day when Mary was told she had immaculately conceived. This would remain the date for centuries, though by Tudor times things would begin to become complicated again.

By the 14th and 15th centuries, the concept of New Yaer’s was turned on its head yet again. There was a gradual re-adoption of 1st January as New Year’s – first in the east, with Lithuania in 1362 and then by Venice, some 150 years later. The change from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar prompted many states to shift to the 1st of January, and soon the chaos of a lack of a unified European New Year’s returned.

This was especially problematic in Britain, as in 1600 the Kingdom of Scotland shifted its New Year’s to January 1st. When James VI became James I, he now ruled over a theoretically United Kingdom with 2 separate New Year’s. Even with the addition of the formal union, the situation did not improve.

William Hogarth painting (c. 1755) which is the main source for “Give us our Eleven Days”, which refers to the Calendar Act of 1750.

Now an actual United Kingdom had two official New Years, causing chaos – especially for the tax man. Something clearly needed to be done and in 1750, parliament passed the Calendar Act. This Act sought to bring the UK in line with the Europe and the Gregorian calendar (but not wanting to associate with anything ‘Catholic’ specifically did not mention the Gregorian calendar itself) and set 1st January as the start of the New Year starting in 1752. This resulted in the rather strangely short year of 1751, where it began on 25 March and ended on 31st December – a span of just 282 days.

New Year’s traditions

I would be remiss if I didn’t briefly touch upon some of the historical traditions associated with the New Year — some still around and others not. Gift giving was a very important part of the New Year, particularly in medieval times.

On the New Year, lords would present opulent gifts to the King in order to gain favour. In return, the King was expected to present lavish gifts as well, to show his kindness and to reward loyalty. This tradition extended into the lower ranks of society as well, but with the shift to 1st January as the New Year this gradually fell in to decline, with Christmas Day becoming the preferred date of gift giving.

One tradition which still remains to an extent –particularly in Scotland with the Hogmanay, is the concept of ‘first-footing.’ As the New Year had perceived pagan roots, the day was considered potentially unlucky. Therefore, it was hoped and prayed that the first person to enter the household in the New Year would be a young, dark-haired man.

This would be a sign of good luck for the coming year. Conversely, if the first entrant was female, blonde or had red hair, this was considered bad luck. The first to enter also followed a ritualised procession. Gifts were meant to be brought (preferably coal, but also mistletoe, money, or bread) and offered as a hope for prosperity in the upcoming year, the coal placed on the fire (bread on the table, presenting of mistletoe and so forth), and the guest to leave through the rear of the house – all without uttering a single word.

But, if you feel any sentimentality towards the old New Years of 25th March I’ll happily squash that right now – 25th March as the New Year still lives on. 6th April is the start of the new tax year (25th March plus the 11 days added on in 1751).

Not all New Years are happy, so make sure to enjoy this approaching one. Happy New Year!