Most of us are familiar with the Lincoln Imp, the mischievous, sinister but somehow likeable mascot of the city. Its figure adorns t-shirts, coffee mugs and even little figurines which can be hung up around the house (including one prominently displayed in my kitchen). It may be surprising, however, that the imp — to many the most identifiable representation of Lincoln — is not only found just in our city but was quite prevalent around the country. One such example is in Grimsby, the story of which I will now share.

The imp at Lincoln Cathedral

There are many tales regarding the mysterious origins of the Lincoln Imp, so for the sake of simplicity I will stick to the one which I find most entertaining. According to the legend (some time in the 13th or 14th century), the devil spawned a pair of mischievous imps to wreak havoc upon the north of England. According to the tale, the imps first attacked Chesterfield, where they wreaked havoc upon the parish church of St. Mary’s, where they twisted the church’s famous spire to its present shape.

They then continued their path of mayhem in Lincoln, entering the cathedral where they began to make a mess of it, turning over furniture, tripping up the Bishop and throwing things about. It was during this time that the angel of The Lord, removing itself from the Bible upon the altar, commanded the imps to halt their wicked ways. One of the creatures, fearful of the angel, duly hid under the altar. The other, however, mocked the angel and began throwing stones at it. The angel, in a fit of anger, cast a spell upon the imp instantly turning it to stone.

According to some tales, this second imp was later frozen in stone by the angel and can be seen on the southern side of Lincoln Cathedral. According to others, however, this second imp was said to have travelled to Grimsby where it entered St James’ Church and began repeating its destructive behaviour. The angel then reappeared and gave the mischievous creature’s backside “a good thrashing” before turning it too into stone.

The Grimsby Imp can still be seen in St. James’ Church clutching its sore bottom.

This story is an enjoyable and fanciful explanation for these two carvings of demonic imps, but the real reason for their existence is much more mysterious and possibly intertwined with paganism. While they may now be best identified with Lincoln (the figures are widely known as ‘Lincoln Imps’ and replicas adorn Lincoln College, Oxford in honour), the figure of the imp is much more common than one may initially think.

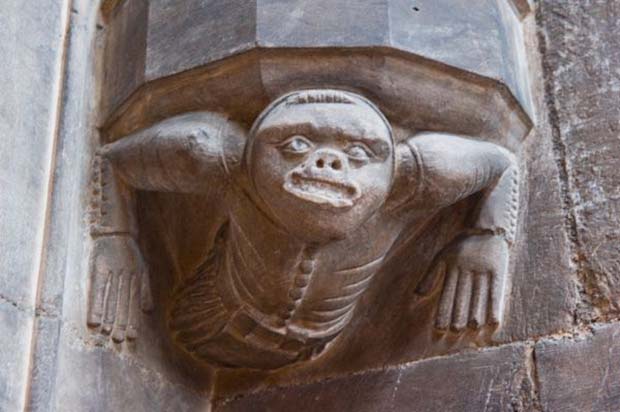

A carved imp in the priest’s room at the Mary’s Church in Beverley.

Besides the figures in the Cathedral and St James’s Church in Grimsby, similar Imps can be seen in the masonry of buildings across northern England and Scotland. Other prominent examples include St Mary’s church in Beverley, East Yorkshire, St. Vigean’s church in Arbroath, Scotland and wooden carvings of the creatures in Stirling Castle. Imps were, in fact, an extremely popular door knocker amongst Britons well into the 19th century and well before the creature became to be identified with our city.

St Vigean’s Church in Scotland also has an imp-like figure.

What is notable about all these examples is their depiction of the imp, with hooves, sharp, pointed teeth, ears from a cow and a hairy body. Also, they all seem to pre-date the modern period, with most carved during the Middle Ages.

The most likely explanation for their existence is as a pagan deity which survived and thrived in the Christian world, much like the famous ‘Green Man‘ (a mysterious face surrounded by and sometimes spewing vegetation, thought to represent rebirth and springtime and argued to be the inspiration for a number of tales including Peter Pan, though that is another story for another day). The imp, therefore is likely similar in nature, perhaps representing a deity associated with agriculture or the keeping of livestock.

Regardless of its obscure origins and prevalence throughout the country, the imp has come to represent Lincoln as its mischievous mascot. So next time you see our little friend perched up in the cathedral, take a moment to ponder its mysterious past. He may not originally be from here, but he has certainly become Lincoln’s favourite little fiend.