With Christmas just around the corner, I thought it would be a good chance to highlight the origins of some of the customs which make up our modern holiday season.

We all know that many of the traditions of the modern Christmas are rooted in traditions nearly as old as the Christian faith itself. What few realise, however, is how much our contemporary celebrations were influenced by our pagan ancestors and in particular our Nordic ancestors – the Vikings.

The influence of the Norse on Lincolnshire is unquestionable. From the 9th to the 11th centuries, Lincolnshire was an important part of the Danelaw, the area of England under Viking control.

A map of the Danelaw.

While Gainsborough took precedence to the northern conquerors (the capital of England that almost was under Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut), Lincoln remained an important trade centre.

Most likely never exceeding roughly 10% of the population of the city, centred around the mercantile areas of the city (roughly those areas where ‘gate,’ the Norse for street, can be seen in the street name –i.e. Michealgate, Danesgate, Hungate, etc.), these Nordic settlers exerted a great deal of influence on many aspects of the lives and culture of the local English inhabitants – and nowhere is this influence more obvious than in the Norse Christmas celebrations.

As most everyone is aware, the original Viking raiders were pagans. Over time, however, like the Angles and Saxons before them, they adopted the Christian faith. As they accepted Christianity as their religion of choice, they adapted many aspects of their earlier festivals and celebrations to fit in with their new faith. This was not a new tactic, as early Christians often worked celebrations around earlier pagan festivals, particularly the Roman Saturnalia, a solstice festival which occurred on December 25th.

The Norse themselves also celebrated the solstice around this period with what they called the Yule festival, and many of those traditional practices were adopted and have made their way into our modern Christmas.

The Christmas tree, wreaths, and mistletoe, for example, all have their roots in Germanic and Norse tradition. Evergreen trees were often decorated, usually with food and statues of the gods, to try and entice the tree spirits of the forest to return from the dead and bring about Spring.

Mistletoe also had mythical importance. Norse legend told of how the god of light, Balder, was slain by an arrow of mistletoe, but was resurrected when his mother’s tears turned the berries of the plant red. It thus represented resurrection and hope for the end of winter.

The Christmas wreath similarly sought to entice the end of the winter, though in contrast to our practice of simply hanging it on a door, the Vikings would set it alight and roll it down a hill, to tempt the return of the Sun.

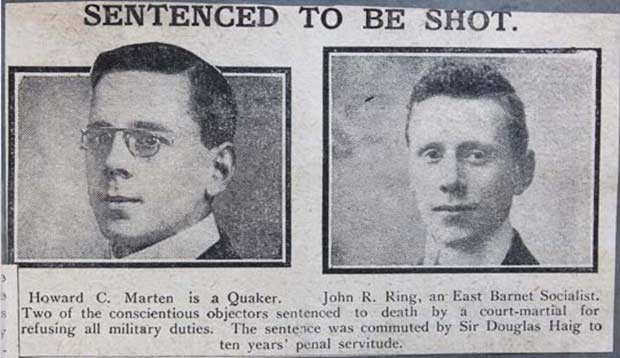

The original ‘Father Christmas’ on his Yule goat.

Perhaps most striking of the Viking traditions which has made it into our modern Christmas is the person of Father Christmas and his reindeer. During the Yule celebrations someone would be selected to dress up as ‘old man winter,’ a white-bearded man dressed in a hooded fur coat, thought to represent Odin.

This individual would travel around the community, joining in with the various celebrations. This figure, when introduced into England, soon became the modern ‘Father Christmas.’

Santa and his reindeer, find their roots in the Norse ‘Yule Goat.’ According to legend, Thor, the god of thunder, rode through the sky in his chariot, pulled by 2 goats.

To celebrate this legend, people would dress in goat skins and travel from house to house, performing songs, playing pranks, telling jokes, or such in exchange for food, drink, or gifts.

These traditions have carried over in todays, Santa Claus and his sleigh, gift giving and carolling (or wassailing).

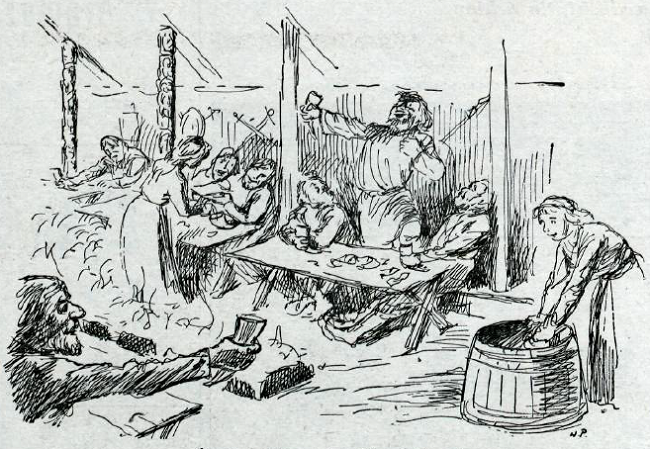

A depiction of a traditional Viking Yule celebration. Image: Reykjavik City Museum

Not all Norse Christmas traditions associated with the ‘Yule goat ’have survived into the modern British festivities, however. One particularly strange custom which has disappeared is what was known as ‘mumming.’ During the mumming period, which lasted from Christmas Eve until the 12th night, young Norse boys would dress in scary masks and costumes, go out at night, and travel the streets terrifying all whom they crossed.

Often, the participants would mimic trolls, ghosts and other mythical creatures. One such occasion was described in 16th century, where a young boy dressed as the Yule goat, complete with ghastly facemask with fully functioning jaw, running through the streets and entering homes, demanding food and gifts for his leaving.

Other aspects of Christmas were also influenced by Viking tradition. The Yule log, for example, now a popular foodstuff, was originally a special log of fir, or yew, which was carved with runes to protect the household from misfortune.

Finally, ham (or more accurately wild boar) was the meal of choice, and the celebrations often revolved around great feasting, even greater drinking, and song.

We owe much of our modern Christmas to the influence of Norse settlers during the Danelaw period. Their influence, however, does not tell the whole story of the holiday season. Next time I will look into Medieval Christmas; how it looked, how ridiculously long it lasted, and the influences of it we still recognise today (even if we don’t associate them with the holiday today).