As anyone who has either grown up or spent an extended amount of time in Lincoln is certainly well aware, our fair city was the birthplace of the modern tank. The recent Lincoln Inspired festival featured several interesting talks; but perhaps none was more interesting from my point of view than that of Richard Pullen, a local historian discussing his book The Landships of Lincoln. Based on his fascinating and entertaining discussion, I thought I would spend a few column inches looking at the history of the tank and the role our city played in its development.

Despite earlier attempts at armoured vehicles, in reality the history of the tank began as the fighting in Europe bogged down. Due to the ongoing stalemate on the front and the excessive casualties of the trench warfare which resulted, by early 1915 the War Office began experiencing with various ‘tench-crossing’ vehicles, most notably the Tritton Trench Crosser, created by William Tritton, managing director of Fosters & Co., an agricultural machinery manufacturer in Lincoln. The design, however, proved too much of a burden and was quickly abandoned. The tank seemed doomed before it even began its life.

The Tritton Trench Crosser in Lincoln

While the War Office took a dim view of the prospects of the concept of an armoured, trench crossing vehicle, The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill saw great potential in the new machines. Establishing the Landships committee in early 1915, he passionately oversaw the development of the tank and argued its cause at the highest levels. These machines were to be ‘landships’ in every sense of the word: they had commanders, not captains, they had hulls and they used navy guns as their primary fire-power.

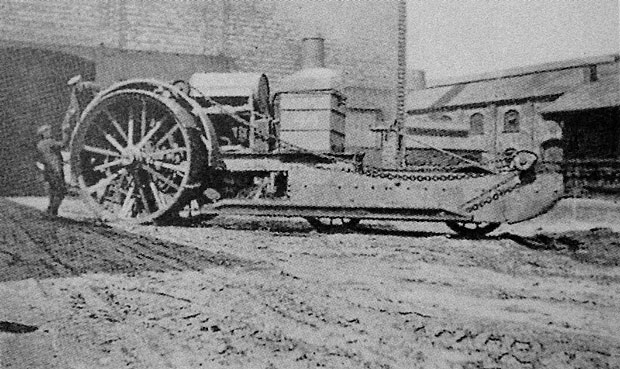

Little Willie, an early design of the tank by William Tritton in Lincoln.

While several manufacturers were mooted to design a prototype, in the end, Fosters was chosen over its rivals, in large part due to the previous designs of William Tritton. While attempts at a grandiose trench crosser quickly failed, soon the ingenious decision to utilize American farming tracks on an armoured car was taken, and within months No.1 Lincoln Machine was tested in early September, 1915. After tweaking the tracks, a new model, nicknamed Little Willie was developed by the end of they year. This design was furthered refined by the first of the Big Willie tanks, nicknamed Mother, which featured a more improved rhomboid design for clearing trenches without getting stuck.

Soon, these tanks were brought into mass production, with the workers (often, as Pullen pointed out, women) famously being told that they were building ‘water tanks for Mesopotamia,’ hence the name ‘tank’. It should be noted that the vast majority of tanks were not built in Lincoln by Fosters. Rather, they were often built in Birmingham, Newcastle or other large industrial centres. When a new model was required, however, the innovation always took place at Fosters and the testing was carried out on what is now Tritton Road. Over the course of the war, Tritton would design and oversee the creation of several different models of tanks, including the Mark IV, the Whippet, and the Hornet.

The Mark IV tank at the Museum of Lincolnshire Life in Lincoln

Despite this great effort in the war, Lincoln often found itself on the outs with regards to receiving the same recognition that other cities often got for their war efforts. By 1916, tanks were popularly used by the War Office as travelling billboards for the selling of war bonds. Often, tanks which had been scarred by action would arrive in town centres and the public would be encouraged to give money for the war effort. Lincoln, however, was continually passed over, until a public campaign finally secured such a visit to Cornhill in early 1918. In that instance, the good people of Lincoln proved their commitment to the war effort by raising over £150,000 for the building of a new destroyer. This was three times the amount originally requested.

The visit of the fund-raising tank was short, and so was the heyday of Fosters’ tank production. On Armistice Day, the contract for the production of tanks was terminated, leaving the company with an excess of materials which they could not use or get rid of, resulting in large losses as the company entered the 1920s. Only a handful more tanks would ever be produced by the company: a tank for the Italian army in 1937 and two tanks for the British army at the start of the Second World War, Tog 1 and Tog 2, both of which were essentially useless.

The sign, placed above the William Foster and Co. factory for a visit by King George. Photo: Lincoln Tank Memorial Group

While the role of Lincoln in the design and production of the tank ended with a whimper, it is still a matter of great pride that our small city played such an important role in the genesis of these all-powerful military machines. It is not just local pride, but as Pullen notes in his book, a great source of family pride, as many people (including Pullen himself) can point to their efforts of their grandparents and great grandparents in the building of these fearsome beasts — a proud legacy which still lives on.