Cory Santos looks at Lincoln’s special twin town which inspired the traditional Christmas Market in the city, as well as the history of a special brew sold for the first time at the market this year.

Lincoln’s special twin

A historic place with Roman ruins and dominated by a large, impressive castle on a steep hill, closely associated with a mythical creature which is prominently carved in stone throughout the town. This may seem like a vague description of Lincoln, but it is instead Neustadt an der Weinstraße: Lincoln’s German twin and inspiration behind the famed Christmas Market currently under way in our city.

The history of twinning towns is by no means a modern construction, with Le Mans in France entering into a partnership with Paderborn in what is now Germany in 1832. It wasn’t until after the Second World War, however, that the concept of twinning really took off.

This golden age of twinning was an attempt at understanding and partnership between cities and former enemies based upon their history and geographical setting. Some connections were somewhat crass and crass, such as the linking of Stalingrad in the USSR with Coventry and Dresden in Germany based upon the link that all had been heavily destroyed during the war, but others proved to be lasting and close bonds. One such was the link forged between Nuestadt and Lincoln in 1969.

Neustadt, or its formal title Neustadt an der Weinstraße (literally translates as “New Town on the Wine Street”), is located in the heart of Germany’s wine growing region near the French border in the Palatine region, formerly associated with Bavaria.

Market square in the centre of Neustadt. Photo: Karl Gritschke

Although the town was only formerly settled in the 1200s, the area had a long line of settlement, with Roman ruins being found throughout. The major castle in the area, Hambach Castle, like Lincoln castle sits prominently on a tall hill, and the Schlossberg (literally “Castle Mountain”) was previously a Roman fort before being turned into a castle by the Carolingian dynasty (think Charlemagne) in the 9th century. The town also has a second castle (much like Lincoln), Wolfsburg castle on its western approaches, but this has been in ruins for a considerable period.

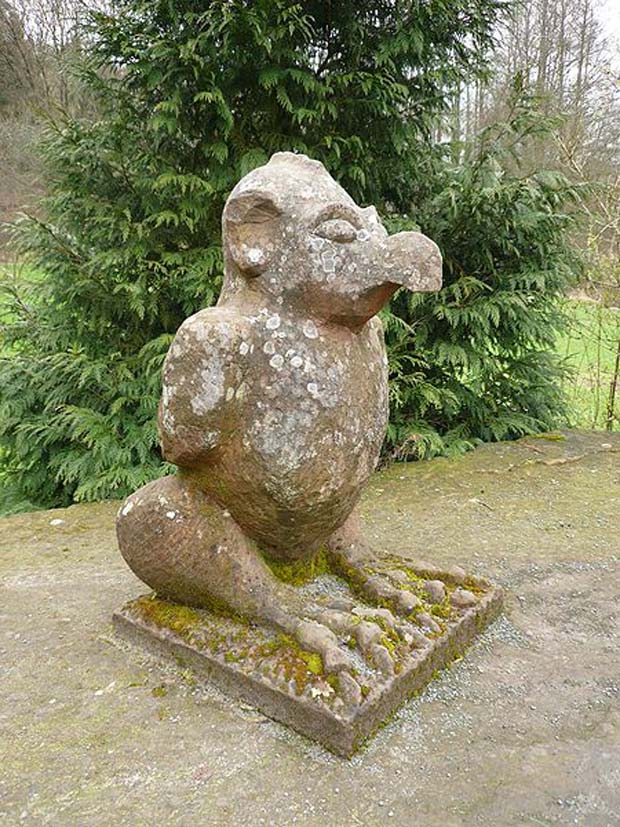

Also similar to Lincoln is Neustadt’s connections with a mythical creature. Like the Imp, the town is the centre of focus for the cryptoid creature known regionally as the Elwedritsch. Prominently carved onto a well in the town centre (as well as several carved eggs throughout the area) these creatures are depicted as a strange combination of a chicken with antlers, and are supposedly the direct result of crossbreeding between chickens and other fowl and the mythical woodland creatures goblins and nyymphs. According to legends, however, their wings are useless and as a result can often be heard rustling in the under brush of the Palatine area.

Statue of an Elwetritsch, a cryptoid creature, a strange combination of a chicken with antlers. Photo; Ramessos

It was these similarities which made the town a perfect twin for Lincoln. Formally twinned in 1969, the two soon found themselves looking for potential closer links and collaboration soon after. The chance finally came in 1982, when members of City of Lincoln Council made a visit to the town.

Witnessing the merriment of the local Christmas market, they decided to import the idea to Lincoln, beginning the Christmas market with some 11 stalls in the Castle Square. While Lincoln’s market has been a resounding success, celebrating 31 years this week and having been copied by many cities and towns throughout the country, the idea of Christmas markets in Britain is something completely new, with Lincoln’s being the first.

The Lincoln Christmas Market now boasts some 300 stalls. Photo: Steve Smailes for The Lincolnite

This concept of Christmas markets is essentially an exclusively Germanic one. Beginning in the 14th and 15th centuries in Southern Germany (particularly Frankfurt and Munich), the custom was begun to usher in the period of Advent with a street market, called the Christkindelsmarkt, or literally “Christ Child Market”.

These markets traditionally sold food, such as Bratwurst and roasted nuts and wine and other seasonal gifts and items such as Zwetschgenmännle (decorated figures made of dried plums) and nutcrackers (the origins of the dreaded tat) and featured traditional songs and dancing. Via the Holy Roman Empire, the tradition then spread throughout much of Northern Europe, particularly to Eastern France, Holland and Belgium and many centuries later, via friendship rather than conquest, to Lincoln and later, the rest of Britain.

The Wassail winner

The Lincoln Christmas Market is also a great place to not only shop for seasonal gifts for loved ones, but get into the festive spirit with traditional Christmas drinks, such as mulled wine. This year, however, stalls will also be selling a popular ancient beverage, brewed and enjoyed during the season for over 1,500 years: Wassail.

A Germanic beverage, Wassail now commonly features a cider base, mulled with cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and sugar, and often topped off with apple slices. The name itself derives from Old English and roughly means “be of good health”, the correct reply being “Drinc Hael!”.

The drink is also closely associated with Wassailing, a traditional event thanking the trees for their bounty and hoping for a greater harvest the following year and later, a Christmas ritual of charity amongst lords and peasants: one which has introduced a number of now-common customs into autumn and winter seasons.

Wassail, an old English tradition for the holiday season. Photo: Jeremy Tarling

While the traditional Wassailing festivals occurred in mid-January (supposedly the twelfth night), after the Norman conquest it began to become much more closely associated with the Christmas season. It was common place for feudal lords to offer the drink to peasants in exchange for their blessings; a charitable deed meant to be perceived separate from begging.

Locals would knock on the door of the noble and sing: “we are not daily beggars that beg from door to door, but we are friendly neighbours whom you have seen before.” After this was sung, the lord was expected to provide the peasants with food and drink, after which the peasants would pay respect to their host by wishing him well and offering their blessings through the following verse:

“Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail too;

And God bless you and send you

A Happy New Year”

It is from this ritualistic practice that two now-common features of the fall and winter seasons are derived. The first (and most obvious) is carolling. The peasants’ reply is a direct ancestor of not only the traditional practice of singing Christmas songs door to door during the festive period, but also the origins of the modern ‘We Wish You a Merry Christmas’.

The second has no relation to Christmas ay all, but a much earlier holiday: Halloween. Besides being associated with good cheer and merriment, Wassailing was also associated with roving bands of ne’er-do-wells and youths who would often demand beverage at various houses, and if they did not receive what they wanted (usually Wassail and figgy pudding) they would vandalize the house as revenge. This, of course, is the origins of the concept of trick or treating (i.e. give us something nice or we’ll give you something nasty).

So, when you visit the Christmas market, please make sure to try the traditional wassail and if you see me, feel free to offer me some along with the toast of ‘waes hael!’ I promise to offer the correct response in return. If you don’t, well you now know the possible rammifications!

Enjoy the Christmas Market everyone!