The idea of a tramway system in Lincoln today would seem extremely difficult to operate. With the sheer volume of vehicles crammed onto streets, laid out in Roman, Viking and Medieval times, there would be little room to run the tracks required. However, just a century earlier, when the motorcar was in its early throws, Lincoln surprisingly had a thriving tram system. What was this system, where did it run and why did it disappear?

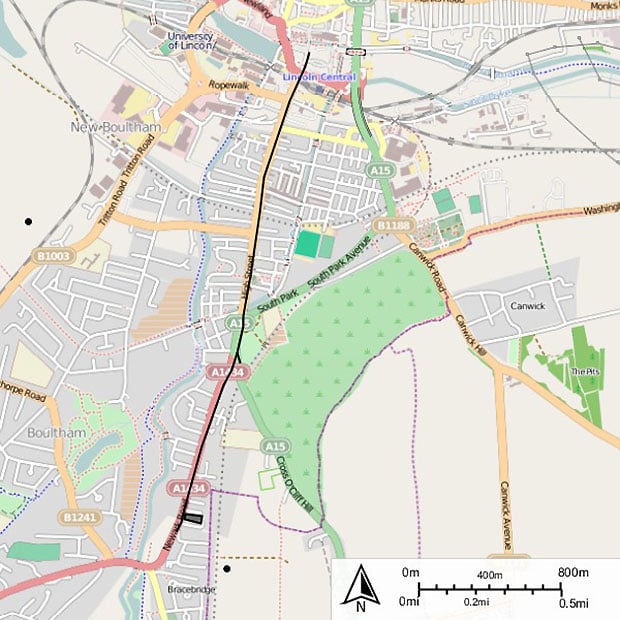

The original idea for a tramway in Lincoln was devised and approved in 1880, after £20,000 of capital had been raised by the Lincoln Tramways Company. The first designs of the system called for two lines within the city: one from Bracebridge to St. Benedict’s Square along Newark Road and the High Street, and another running from Carholme to the Arboretum. For unknown reasons, but probably due to financial difficulties, only the line along the High Street was built, being completed and opened for business on 8 September 1882.

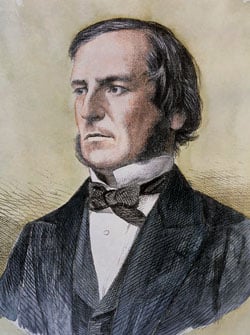

The last Lincoln horse tram, whose driver died in an electrical shock incident. Photo: Tramways and Light Railway Society

The trams were single carriage and held between 16 and 32 passengers, depending on the car in operation. Set on rails and pulled by horses, the trams took roughly 20 minutes from their depot on the corner of Newark Road and Ellison Street (the building was known as the ‘Tram Stables’) to St. Benedict’s Square, with the only stop being Cranwell House (located by St. Botolph’s Church), although like any other mode of travel in the city it would often have to stop at the level crossings. The service was fairly successful, but really became a hit with the people of Lincoln when , in 1901, a half-penny charge was introduced for workers.

Despite the success of the horse trams, the city soon sought to remove them from the streets. This was due to the rise of electrically powered trams throughout Britain, a trend the city council wanted to emulate. As a result, in 1905 they purchased the line from the Lincoln Tramways Company, establishing Lincoln Corporation Tramways and beginning to electrify the lines.

The method for electrifying the trams was a system of studs placed along the High Street, a system rarely seen elsewhere in England (the only other instance I could find was on Mile End Road in East London). This system, known as the Griffiths-Bedell stud system was very advanced, but unfortunately also very susceptible to failure, sometimes in spectacular fashion. Whereas previously the citizens of Lincoln would be liable to avoid the menace that was horse droppings, now they occasional had to avoid the tracks inspection boxes on the High Street, which exploded around them!

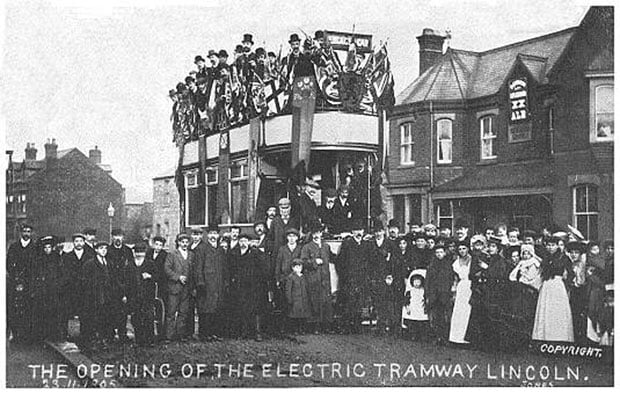

The opening of the electric tram line in Lincoln in 1905 was a big event for the city. Photo: John R. Prentice collection

The reasons for these explosions were a combination of the studs, the tram cars and a nasty gas leak. Gas from the mains would occasionally seep into the electrical conduit which ran along the route and when the metal brush of the tram sparked on the studs, with the results being spectacular (and dangerous!).

Such was the case on 6 June 1908 when one Mrs. Blatherwick was struck and injured in one such explosion. The studs proved faulty in other non-explosive ways as well, as various bits of metal on the road would often come into contact with the studs and the trams, shorting the lines and shutting down the system. As a result, in 1919 overhead lines were installed, to minimize the dangers and faults of the service.

Regardless of the dangers involved, the electrification of the trams proved an instant success. Within the first week of service, over 3,000 journeys had been made on it. The travel times as well were much improved with electrification: 15 minutes from Bracebridge to Cornhill, rather than the 20 minutes plus with the horse drawn service.

Map of the route of the Lincoln tram system.

What success the tram achieved, however, waned shortly after the end of the First World War. With the increased availability and affordability or motor cars, the trams quickly became more of a white elephant than an important mode of transport. As a result, the system was officially closed in 1928, never to return.

The idea of a new tram system in Lincoln sounds enticing. But the reality is that unless the High Street is pedestrianised completely or some other city-changing public works occur, modern Lincoln and its medieval streets simply could not cope with it. The story of the trams, however, does represent a great period of British history — when private and public enterprises flouted costs in a constant battle of technological one-upmanship.

A model of a Lincoln tram built especially in Bristol for Richard Woods’ family. Photo: Richard Woods