The village of Langton-by-Wragby was a quiet backwater in the Middle Ages. In fact, the modern-day village, just past Wragby on the road to Horncastle, still remains a tiny, peaceful settlement. The village, however, would play a pivotal role in the history of England, its politics and its monarchy, when in 1215, one of its sons, along with a group of rebellious barons, forced the king to sign an important treaty limiting the powers of the monarchy.

The Magna Carta

The treaty was Magna Carta and the man was Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury. Stephen Langton was born sometime around 1150. Although born in a rural setting, Langton was hardly a peasant. His father, Henry, was the Lord of the Manor of the village and his two siblings both found success in life: Simon as Archbishop-elect for York (which was overturned by the Pope) and later Archdeacon of Canterbury, and the other, Walter, as a knight and crusader.

Amongst this family backdrop of privilege and success however, no Langton’s star shined brighter than Stephen’s. His early career saw him positioned in York, but his arrival at the University of Paris around 1181 saw his religious stock rise ever higher. He studied and then began teaching there, quickly becoming an eminent theologian. This high standing among those in the church, as well as friendships which he had formed in Paris, soon saw Stephen rising further up the ranks of the Catholic faith.

Stephen Langton, immortalised on Lincoln Cathedral.

One of his closest friends, Lotario de’Conti, later known as Innocent III, had been elected Pope in 1198. He called Langton to Rome in 1206 and made him Cardinal-priest of San Crisogono church, the highest rank in the church hierarchy below that of the pontiff. With his new rank and the continued backing of the Pope, Stephen became recognised as foremost of all English clerics, a position that would soon see him thrust head first into a battle between the King of England and the Church.

The election of a new Archbishop of Canterbury following the death of Hubert Walter in 1205 had devolved into an open struggle between the monks of Canterbury Cathedral — who wanted to appoint one of their own, Reginald — and King John — who wanted the Bishop of Norwich, a political ally, appointed. To the King, the appointment of the Archbishop was his right and had been exercised by all other monarchs since the conquest. The growing power of the papacy, however, wanted control over its affairs in England back and Innocent III ordered a re-election to be held in Rome in 1207, where Stephen Langton was duly elected (probably with the Pope giving the monks a bit of a nudge).

King John, furious at the attack on his political powers, proclaimed anyone who sided with the new archbishop a public enemy, expelling the monks of Canterbury and forcing Langton to remain in exile in Burgundy, under the protection of Philip II of France. Innocent III, becoming increasingly agitated with the behaviour of John, placed England under interdict (a censure denying sacraments to those affected) in 1208, then later in 1213 he excommunicated John and called for his deposition.

St Giles Church in Langton, where the story of the Magna Carta begins.

Under mounting pressure at home, John relented and in 1213, Stephen Langton was finally able to take up his position as Archbishop of Canterbury. His first act was to absolve the King for his wrong deeds, which he duly completed after promises from King John that the unjust laws he had created were overturned and certain liberties afforded to the nobility and church under Henry I be reinstated.

To John, reconciliation with the church was not undertaken to save his soul, but rather, save his throne. His military activities in France had proved disastrous, with massive losses of land, most notably the capture of Normandy by the French in 1204. By 1213, fear of a French invasion was not unfounded, so bowing to papal demands ensured John a powerful ally who could keep the French at bay.

John’s problems, however, were just as bad in England as they were in France. In order to fund his series of military failures on the continent, John was forced to place ever-increasing burdens upon his subjects in the form of taxation and levies at a level never before witnessed in England. This resulted in several unjust laws and practices, created by the king, which harshly punished the barons and peasants of the country and left many heavily burdened with debt to the crown. It was these laws and practices which Stephen Langton had made the king swear to repeal upon his arrival from exile. The king, however, was desperate and quickly reneged on his promise.

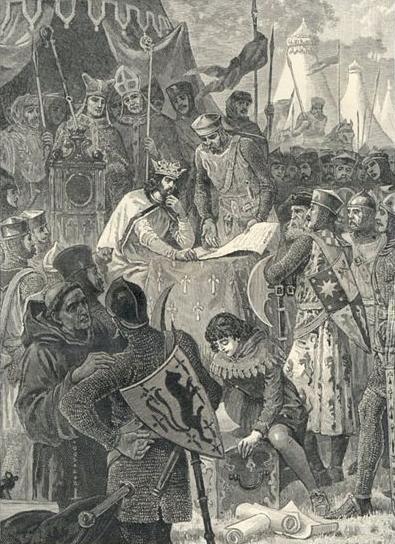

King John signing the Magna Carta, with Archbishop Langton looking on.

Langton, aggravated by the brazen nature of the monarch and his disregard for his oath, openly began to preach against the monarch, calling for a return to the Charter of Liberties of Henry I’s reign, some 80 years previous; this period, where law and justice were championed had become seen as something of a ‘golden age’ amongst the nobility of England. By 1215, Langton had joined forces with the barons, who were by now openly rebellious, and called for John to sign a treaty confirming his acceptance of their demands.

The document, now known as Magna Carta, was drafted by Langton and called for the limitation of royal power and the elimination of arbitrary will in judgement by the monarch, essentially reinstating the Charter of Liberties of Henry I. With the power of the church under Langton united with the military might of the barons, John had no choice but to sign the document on June 15, 1215.

Although Magna Carta was short-lived in its powers at the time (the Pope nullified it after protestations from John), it was an important blow against the tyranny of absolute monarchs like John. Few documents have had such an important impact on the legal history of not only England and Britain as a whole, but also the wider world, particularly in the former colonies.

With the upcoming Independence Day celebrations for the US this week, it’s worth remembering that the inspiration for their Bill of Rights, the Magna Carta, was created by a Lincolnshire lad, from a tiny village, just outside Wragby on the A158.

Lincoln is the only place in the world where you can find an original copy of Magna Carta together with the Charter of the Forest, issued in 1217 to amplify Magna Carta and is one of only two surviving copies. The documents belong to Lincoln Cathedral and are housed in Lincoln Castle, a seat for justice from its beginnings. Plans are underway for the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, including a new home for the exhibition within the Castle, as part of the Lincoln Castle Revealed project.